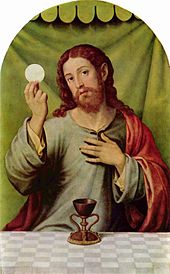

The institution of the Eucharist has been a key theme in the depictions of the Last Supper in Christian art,[1] as in this 19th century Bouveret painting.

There are different interpretations of the significance of the Eucharist, but "there is more of a consensus among Christians about the meaning of the Eucharist than would appear from the confessional debates over the sacramental presence, the effects of the Eucharist, and the proper auspices under which it may be celebrated."[2]

The phrase "the Eucharist" may refer not only to the rite but also to the consecrated bread (leavened or unleavened) and wine or, unfermented grape juice (in some Protestant denominations) or water (in Mormonism), used in the rite,[4] and, in this sense, communicants may speak of "receiving the Eucharist", as well as "celebrating the Eucharist".

Names and their origin

Eucharist, from Greek εὐχαριστία (eucharistia), means "thanksgiving". The verb εὐχαριστῶ, the usual word for "to thank" in the Septuagint and the New Testament, is found in the major texts concerning the Lord's Supper, including the earliest:For I received from the Lord what I also delivered to you, that the Lord Jesus on the night when he was betrayed took bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it, and said, "This is my body which is for you. Do this in remembrance of me." (1 Corinthians 11:23-24)The Lord's Supper (Κυριακὸν δεῖπνον) derives from 1 Corinthians 11:20-21.

When you come together, it is not the Lord's Supper you eat, for as you eat, each of you goes ahead without waiting for anybody else. One remains hungry, another gets drunk.Communion is a translation; other translations are "participation", "sharing", "fellowship"[5] of the Greek κοινωνία (koinōnía) in 1 Corinthians 10:16. The King James Version has

The cup of blessing which we bless, is it not the communion of the blood of Christ? The bread which we break, is it not the communion of the body of Christ?[6]

Terminology for the Eucharist

- "Eucharist" (noun). The word is derived from Greek "εὐχαριστία" (transliterated as "eucharistia"), which means thankfulness, gratitude, giving of thanks. Today, "the Eucharist" is the name still used by the Eastern Orthodox, the Oriental Orthodox, Roman Catholics, Anglicans, Reformed/Presbyterian, United Methodists, and Lutherans. Other Protestant traditions rarely use this term, preferring either "Communion", "the Lord's Supper", or "the Breaking of Bread".

- "The Lord's Supper", the term used in 1 Corinthians 11:20. Most denominations use the term, but generally not as their basic, routine term. The use is predominant among Baptist groups, who generally avoid using the term "Communion", due to its use (though in a more limited sense) by the Roman Catholic Church. Many evangelical Anglicans will often use this term rather than "Eucharist".

- "The Breaking of Bread", a phrase that appears in the New Testament in contexts in which, according to some, it may refer to celebration of the Eucharist: Luke 24:35;Acts 2:42, 2:46, 20:7; 1 Corinthians 10:16.

- "Communion" (from Latin communio, "sharing in common") or "Holy Communion",[7] used, with different meanings, by Roman Catholics, Orthodox, Anglicans, and many Protestants, including Lutherans. Orthodox, Catholics, Anglicans, and Lutherans apply this term not to the Eucharistic rite as a whole, but only to the partaking of the consecrated bread and wine, and to these consecrated elements themselves. In their understanding, it is possible to participate in the celebration of the Eucharistic rite without necessarily "receiving Holy Communion" (partaking of the consecrated elements. Most groups that originated in the Protestant Reformation usually apply this term instead to the whole rite. The meaning of the term "Communion" here is multivocal in that it also refers to the relationship of the participating Christians, as individuals or as Church, with God and with other Christians (see Communion (Christian)).

- "Mass", used in the Latin Rite Roman Catholic Church, Anglo-Catholicism, the Church of Sweden, the Church of Norway and some other forms of Western Christianity. Among the many other terms used in the Roman Catholic Church are "Holy Mass", "the Memorial of the Passion, Death and Resurrection of the Lord", the "Holy Sacrifice of the Mass", and the "Holy Mysteries".[8]

- The "Blessed Sacrament" and the "Blessed Sacrament of the Altar" are common terms used by Roman Catholics, Anglicans, and Lutherans for the consecrated elements, especially when reserved in the Church tabernacle. In The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints the term "The Sacrament" is used of the rite. "Sacrament of the Altar" is in common use also among Lutherans.

- "The Divine Liturgy" is used in Byzantine Rite traditions, whether in the Eastern Orthodox Church or among the Eastern Catholic Churches. These also speak of "the Divine Mysteries", especially in reference to the consecrated elements, which they also call "the Holy Gifts".

- The "Divine Service" is the title for the liturgy used in Lutheran churches and is used by most conservative Lutheran churches to refer to the Eucharist.

- In Oriental Orthodoxy the terms "Oblation" (Syriac, Coptic and Armenian Churches) and "Consecration" (Ethiopian Church) are used. Likewise, in the Gaelic language of Ireland and Scotland the word "Aifreann", usually translated into English as "Mass", is derived from Late Latin "Offerendum", meaning "oblation", "offering".

- The many other expressions used include "Table of the Lord" (cf. 1 Corinthians 10:16), the "Lord's Body" (cf. 1 Corinthians 11:29), "Holy of Holies".

History

Further information: Origin of the Eucharist

Biblical basis

The Last Supper appears in all three Synoptic Gospels: Matthew, Mark, and Luke; and in the First Epistle to the Corinthians,[2][9][10] while the last-named of these also indicates something of how early Christians celebrated what Paul the Apostle called the Lord's Supper. As well as the Eucharistic dialogue in John chapter 6.Paul the Apostle and the Lord's Supper

In his First Epistle to the Corinthians (c 54-55), Paul the Apostle gives the earliest recorded description of Jesus' Last Supper: "The Lord Jesus on the night when he was betrayed took bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it, and said, 'This is my body which is for you. Do this in remembrance of me.' In the same way also the cup, after supper, saying, 'This cup is the new covenant in my blood. Do this, as often as you drink it, in remembrance of me'." [11]Gospels

The synoptic gospels, first Mark,[12] and then Matthew[13] and Luke,[14] depict Jesus as presiding over the Last Supper. References to Jesus' body and blood foreshadow his crucifixion, and he identifies them as a new covenant.[15] In the gospel of John, the account of the Last Supper has no mention of Jesus taking bread and wine and speaking of them as his body and blood; instead it recounts his humble act of washing the disciples' feet, the prophecy of the betrayal, which set in motion the events that would lead to the cross, and his long discourse in response to some questions posed by his followers, in which he went on to speak of the importance of the unity of the disciples with him and each other.[15][16]Agape feast

The expression The Lord's Supper, derived from St. Paul's usage in 1 Corinthians 11:17-34, may have originally referred to the Agape feast, the shared communal meal with which the Eucharist was originally associated.[17] The Agape feast is mentioned in Jude 12. But The Lord's Supper is now commonly used in reference to a celebration involving no food other than the sacramental bread and wine.Early Christian sources

The Didache (Greek: teaching) is an early Church order, including, among other features, instructions for Baptism and the Eucharist. Most scholars date it to the early 2nd century,[18] and distinguish in it two separate Eucharistic traditions, the earlier tradition in chapter 10 and the later one preceding it in chapter 9.[19][20] The Eucharist is mentioned again in chapter 14.[21]Ignatius of Antioch (ca. 35 or 50-between 98 and 117), one of the Apostolic Fathers,[22] mentions the Eucharist as "the flesh of our Saviour Jesus Christ",[23] and Justin Martyr speaks of it as more than a meal: "the food over which the prayer of thanksgiving, the word received from Christ, has been said ... is the flesh and blood of this Jesus who became flesh ... and the deacons carry some to those who are absent."[24]

Eucharistic theology

Many Christian denominations classify the Eucharist as a sacrament.[25] Some Protestants prefer to call it an ordinance, viewing it not as a specific channel of divine grace but as an expression of faith and of obedience to Christ.Most Christians, even those who deny that there is any real change in the elements used, recognize a special presence of Christ in this rite, though they differ about exactly how, where, when, and why Christ is present.[26] Roman Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy, and the Church of the East teach that the consecrated elements truly become the body and blood of Jesus Christ. Transubstantiation is the metaphysical explanation given by Roman Catholics as to how this transformation occurs. Lutherans believe that the body and blood of Jesus are present "in, with and under" the forms of bread and wine, a concept known as the sacramental union. The Reformed churches , following the teachings of John Calvin, believe in a immaterial, spiritual (or "pneumatic") presence of Christ by the power of the Holy Spirit and received by faith. Anglicans adhere to a range of views although the teaching on the matter in the Articles of Religion conforms with continental Reformed theology. Some Christians reject the concept of the real presence, believing that the Eucharist is only a memorial of the death of Christ.

The Baptism, Eucharist and Ministry document of the World Council of Churches, attempting to present the common understanding of the Eucharist on the part of the generality of Christians, describes it as "essentially the sacrament of the gift which God makes to us in Christ through the power of the Holy Spirit", "Thanksgiving to the Father", "Anamnesis or Memorial of Christ", "the sacrament of the unique sacrifice of Christ, who ever lives to make intercession for us", "the sacrament of the body and blood of Christ, the sacrament of his real presence", "Invocation of the Spirit", "Communion of the Faithful", and "Meal of the Kingdom".

Ritual and liturgy

Anglican

In most of the national or regional churches of the Anglican Communion, the Eucharist is now celebrated every Sunday, having replaced Morning Prayer as the principal service. The rites for the Eucharist are found in the various prayer books of Anglican churches. Wine along with wafers or bread are used. Daily celebrations are now the case in most cathedrals, and many parish churches will offer Eucharistic services multiple times a week. There are now only a small minority of parishes with a priest where the Eucharist is not celebrated at least once each Sunday. The nature of the ceremony with which it is celebrated, however, varies according to the orientation of the individual priest, parish, diocese or regional church.Protestants

Baptist

The bread and "fruit of the vine" indicated in Matthew, Mark and Luke as the elements of the Lord's Supper[32] are interpreted by many Baptists as unleavened bread (although leavened bread is often used) and, in line with the historical stance of some Baptist groups (since the mid-19th century) against partaking of alcoholic beverages, grape juice, which they commonly refer to simply as "the Cup".[33] The unleavened bread, or matzoh, also underscores the symbolic belief attributed to Christ's breaking the matzoh and saying that it was his body. Baptists do not hold Communion, nor the elements thereof, as sacramental; rather, it is considered to be an act of remembrance of Christ's atonement, and a time of renewal of personal commitment.Since Baptist churches are autonomous, Communion practices and frequency vary among congregations. In many churches, small cups of juice and plates of broken bread are distributed to the seated congregation by a group of deacons. In others, congregants proceed to the altar to receive the elements, then return to their seats. A widely accepted practice is for all to receive and hold the elements until everyone is served, then consume the bread and cup in unison. Usually, music is performed and Scripture is read during the receiving of the elements.

Some Baptist churches are closed-Communionists (even requiring full membership in the church before partaking), with others being partially or fully open-Communionists. It is rare to find a Baptist church where The Lord's Supper is observed every Sunday; most observe monthly or quarterly, with some holding Communion only during a designated Communion service or following a worship service.

No comments:

Post a Comment